Your Protection Doesn’t Protect Me

In 2021, CREA led the consortium campaign from Women Gaining Ground (WGG), Your Protection Doesn’t Protect Me. It launched on 25 November with the message:

People with full rights don’t need protection, they demand lives free of violence. We need to dismantle structures that exclude people based on gender and enable access to services, information, and justice.

2021 marks the 30th anniversary of the global 16 Days of Activism campaign against gender-based violence (GBV). As we recommit to ending GBV every day, we also assert that feminist movements, policymakers, legal bodies, and institutions must find more affirmative approaches to move forward.

To end GBV, we want rights-based solutions NOT protectionist approaches. Girls and women, including those with disabilities, trans and non-binary persons are indispensable change-makers when they are empowered to explore, discuss, and act on GBV issues both locally and globally.

In 2021, CREA is worked via the Women Gaining Ground consortium with Akili Dada, IWRAW Asia Pacific, and partners in Bangladesh, India, Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda to highlight Your Protection Doesn’t Protect Me. Over the course of two weeks, we heard from global South-based activists, particularly girls and women with disabilities, about why protectionist approaches to end GBV don’t serve their realities, and the rights-affirming ways forward they want to see instead.

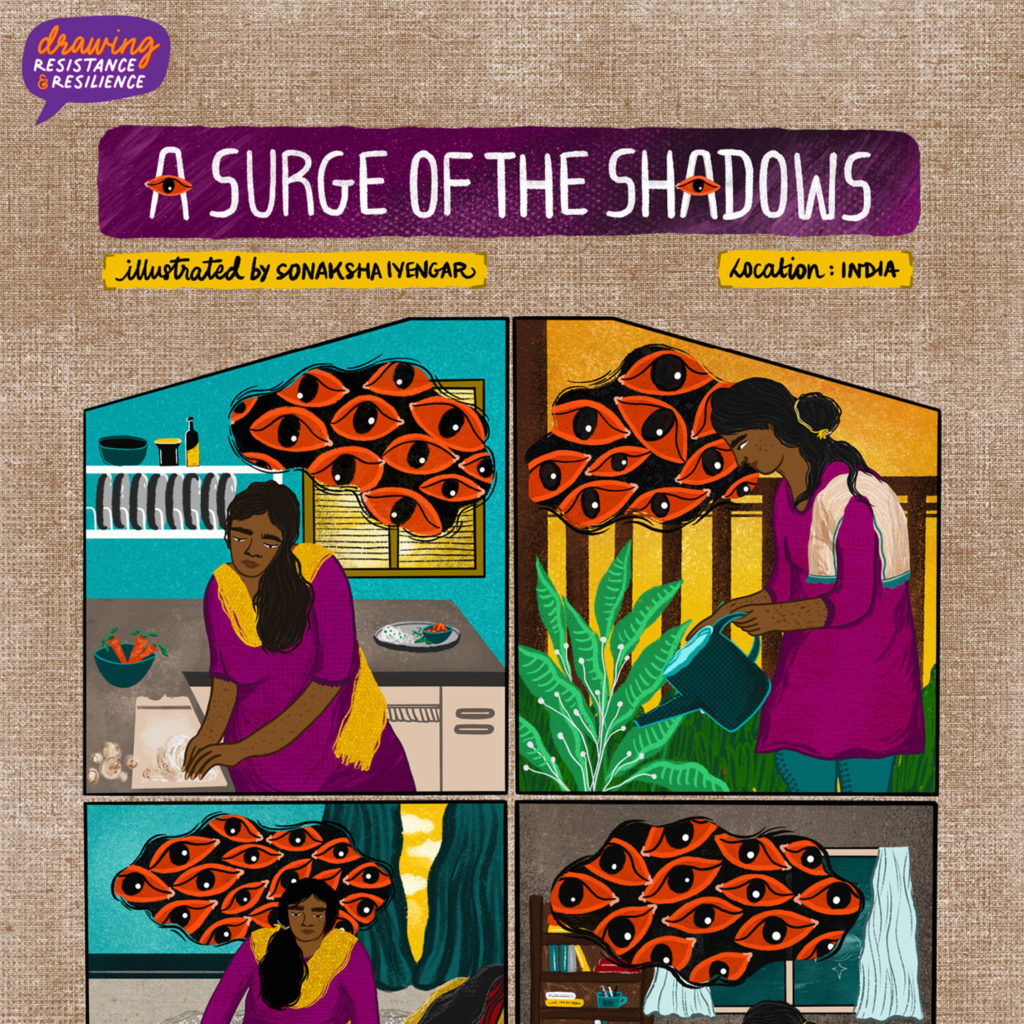

1. A Surge of the Shadows

Go digital but retain link between online & on-ground services to tackle gender-based violence.

Across the world, COVID-19 induced lockdown accelerated the rise in deteriorating mental health conditions among people and anxieties stemming from severe economic distress. In addition, psycho-social conditions caused from being locked within small spaces created a volatile and toxic environment leading to an increase in gender based violence (GBV).

Kahi Ankahi Baatein (KAB) is a 24×7 mobile phone based IVRS infoline that provides information on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) and GBV in Hindi to girls, women and transpersons. This AWC program is implemented by CREA in India and has a nationwide reach. KAB, being a telecommunications-dependent intervention, continued its work during the lockdown. However, limitations like lack of privacy for the user to access confidential services and the cutting off of on-ground emergency response mechanisms needed to mitigate GBV– community support, peer outreach, safe housing and transport options, mental and physical health services and access to justice – soon emerged, prompting KAB to reach out to CREA partners and explore including new features and adapting some of its content to respond to the crisis.

KAB started curating and disseminating information on helplines/hotlines for GBV and clinics that offer SRHR and GBV related services in partnership with Family Planning Association of India. Alongside, an online counselling cum referral platform was developed by CREA, TARSHI and Gram Vaani to serve as a one stop service for counselling on GBV and SRHR in multiple languages across India.

The need for digital platforms that address GBV related issues during emergencies emerged as a learning along with the importance of foregrounding the online-offline linkages between relief mechanisms and not seeing it as an either/or option.

Artwork by Sonaksha Iyengar.

Story curated by CREA.

View the illustrated story here.

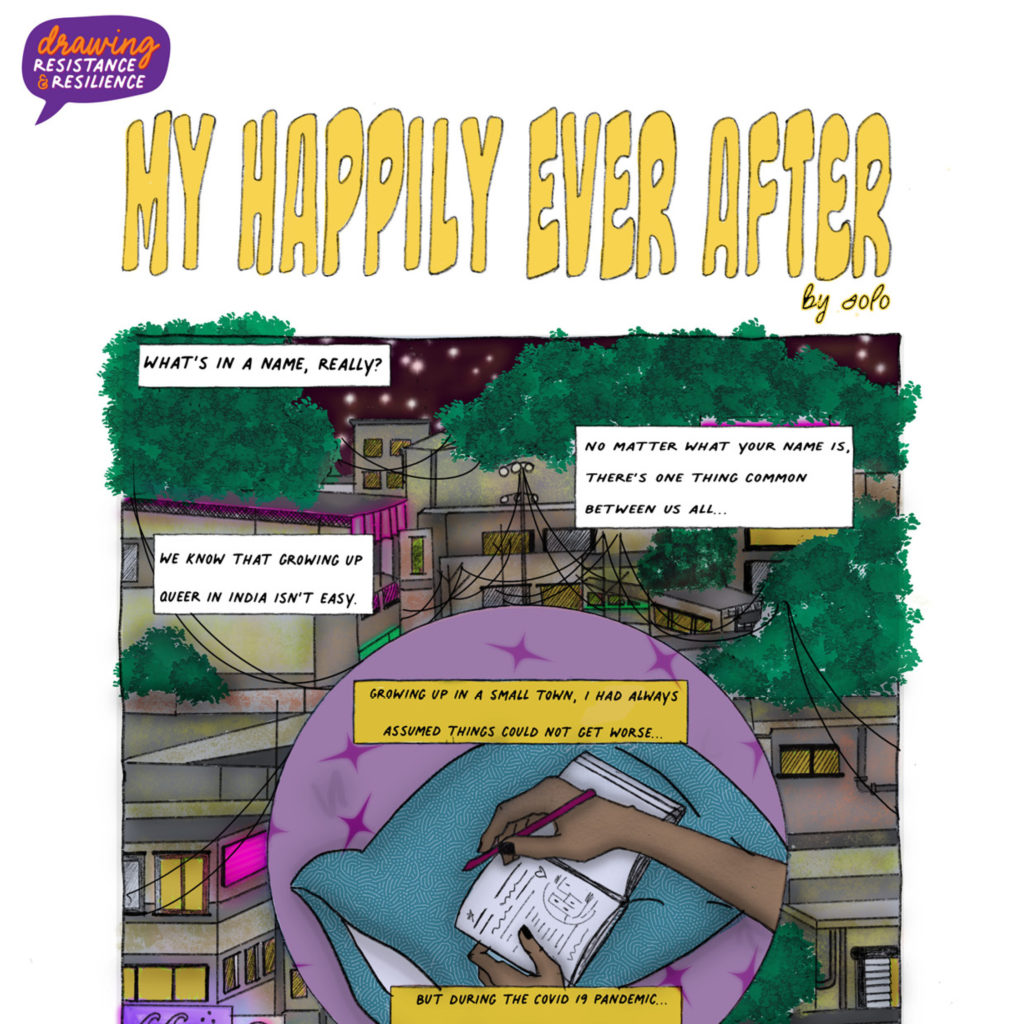

2. My Happily Ever After

We need safe houses for queer and trans persons escaping persecution during COVID-19.

TW: sexual violence

While many of us ‘stayed home, stayed safe’ due to the COVID-19 pandemic, ‘homes’ did not come with familiality or security for queer persons. TS, a final year arts student in Ranchi, Jharkhand, was asleep in her room in the family house, when she heard her family members planning her marriage with a boy without having sought her consent. TS, who identifies as lesbian, bravely confronted her family and shared the same with them. What followed over the next 3 days, before TS escaped from her home/prison, is best left unsaid.

TS reached out to a local support group for queer women (not named here for security reasons), she had first known about the group in 2019 through the campaign ’16 Days of Activism’, and with their support, TS negotiated her return to her family house (she no longer refers it as home) as she had nowhere to go due to the lockdown. Even though her family did not physically assault her upon her return because TS had told them she is in touch with the police, she was put through conversion regiments, poojas etc. It was when she heard her father and brother plan her sexual assault by multiple men in order to convert her, she knew she could no longer stay in that house. TS was lucky and brave enough to escape again! But the onus of surviving families should not fall upon individuals in the first place.

Queer and trans persons need community run safe spaces (not modelled after state run rescue homes), especially in the light of the pandemic, where they can seek refuge from persecution.

Artwork by Solo.

Story curated by CREA.

View the illustrated story here.

3. When Safe Spaces are Disrupted

Outed without consent during the lockdown.

In countries like Morocco where LGBTQ+ rights discourse has not advanced considerably, the queer and trans community lives precariously. Living without outing oneself is a practice in queerness for most people so when that is sacrificed, lives are put in jeopardy.

In one case documented by an AWC partner working in Morocco, a certain individual outed members from the community during the lockdown putting them at risk of confinement, violence and loss of income. In addition, those who had to go back to their natal homes during the lockdown, faced homophobia and familial violence.

Our partners started offering psycho-social support online along with essential supplies to those fleeing persecution at home. The need for psycho-social support being available online in countries where physical access to support networks is limited was affirmed.

Artwork by Ishita Mehra.

Story curated by AFE.

View the illustrated story here.

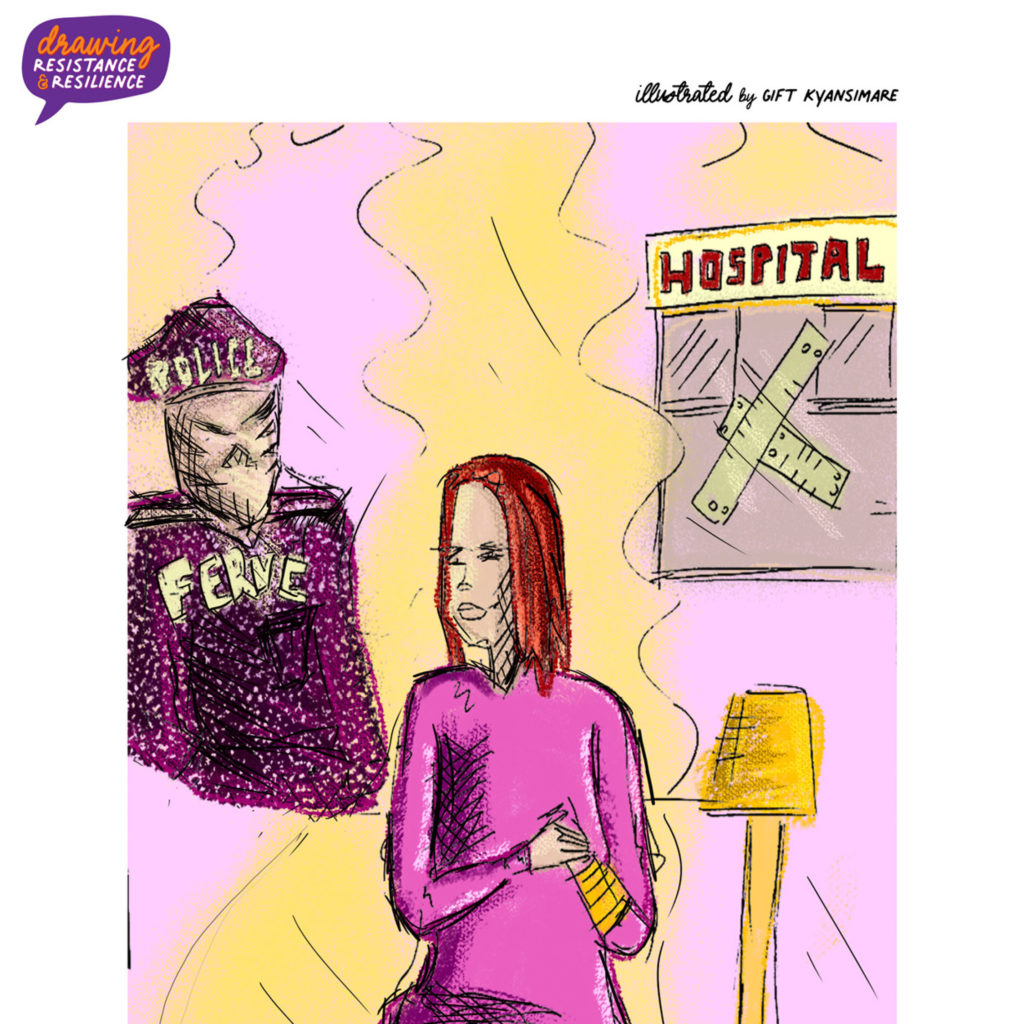

4. What’s in your bag

State and police violence towards sex workers during COVID-19.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on marginalized communities. For sex workers in Tanzania, their access to healthcare, most critically to ART/PREP medication, was cut off as hospitals focused solely on COVID-related care and mobility was policed. In one case documented by our partners, an HIV positive sex worker who could not afford and access ART medication due to lack of funds and availability succumbed to the condition.

A program was started by our partners where sex workers could go and pick up medication for their peers and deliver it to them. However, high transportation costs during the lockdown and police hostility limited the reach and effectiveness of the program.

Police brutalities intensified as access to legal remedies was cut off due to shutting down of courts during the lockdown and sex workers could not negotiate their safety from the police by paying bribes with money and sex.

Community led organizations came to a conclusion that decriminalization is a prerequisite for survival of the community during emergencies alongside sensitizing the police on sex work. And developing additional skills and streams of income generation as well as uninterrupted access to healthcare was the solution for mitigating crises of this nature.

Artwork by Gift Kyansimare.

Story curated by UHAI-EASHRI.

View the illustrated story here.

5. Tech-it-easy

Sensitizing systems on sex work for better emergency response.

Measures to curb the spread of COVID-19 in Kisumu County, Kenya included closure of bars, hotels, and other social premises, as well as an emphasis on social distancing. This adversely affected the sex worker population that could not find clients at their usual hotspots and had to go to their clients’ homes putting them at a higher risk of violence.

Three sex workers were killed while over 148 reported cases of gender-based violence (GBV) were recorded. The criminalization of sex work meant reduced access to justice and many sex workers were afraid to report incidences of violence at the gender desks at police stations. SRHR and HIV services were hampered putting the lives of those living with HIV at risk. Our partners working in Kisumu mitigated the crisis by:

- Mental and physical health: Setting up centers to provide psycho-social and physical health support during the lockdown.

- Responding to violence: Setting up hotlines for GBV and working together with the police and health centers to ensure quick response.

Our partners in Kisumu were successful in sensitizing the police, health and administrative systems on sex work over the years which made conducting the relief work with their support possible.

Artwork by Nancy Chelagat.

Story curated by UHAI-EASHRI.

View the illustrated story here.

6. How does anyone even sleep anymore

Access to justice cannot be locked down during emergencies.

If there is one thing governments around the world should have but did not ‘lock down’ during the COVID-19 pandemic, was admitting more persons into prisons. Ignoring calls from organizations working on prison reforms across the world to release under-trials and persons in prison who are at risk because of their age and health conditions, governments of the world continued incarcerating more people, putting them and existing prison populations at risk of catching the coronavirus.

In Egypt where homosexuality remains criminalized, our partner AFE, which works on legal and mental-physical health support for marginalized populations including LGBTQI+ persons and LGBT refugees, struggled to provide support to queer and trans populations arrested during the lockdown for their gender and sexual identities/practices. As justice systems remained shut due to COVID, those arrested could not seek bail or access justice when they faced gender based and custodial violence in prisons. In a custodial violence case documented, a queer person was handcuffed to another person who was COVID positive in a prison.

Even as Courts in Egypt have opened up, they are dealing with an overwhelming number of pending cases by assigning cases of gender-based violence (GBV) to non-criminal appellates who have no experience in dealing with cases of GBV. Outside the prison, our partner supported those facing gender based violence by employing methods of monetary support, counseling survivors through voice notes and text messages when their communication access was limited, and providing relocation services to those facing violence at home. Need for justice systems to remain accessible during emergencies emerged as a critical requirement for mitigating extreme violence.

Note: At CREA, we view crimes against queer, transgender, non-binary, disabled and sex worker populations along with custodial violence as facets of gender based violence.

Artwork by Solo.

Story curated by AFE.

View the illustrated story here.

7. We are stronger together

For sex workers, mobility is safety.

In Uganda, the COVID-19 pandemic changed the gender-based violence (GBV) context in a way that lockdowns, curfews and social isolation exposed sex workers in their different diversities (gender, race, tribe, class) to violence and coercion. They were unable to escape abusive partners due to restrictions on mobility.

Alongside, financial vulnerability forced them to endure various gender-based violations as criminalization further inhibited the community’s ability to report crimes perpetrated by clients and former partners. Further still, the lock down forced most of the sex workers to operate from their homes exposing them to gender-based violations from neighboring communities.

AWC partners mitigated the crisis by training community leaders to identify GBV survivors and refer GBV victims to appropriate available support. They also trained paralegals who were staged at different catchment areas covering a number of hotspots where members operate or stay.

Partners accessed a Ministry of Health support that enabled them to use the organizational vehicle and reach out to survivors for violence related support such as physical counseling, transporting members to safe spaces, medication and mediation services. Mobility as key to safety in times of emergencies emerged as a key learning.

Artwork by Nancy Chelagat.

Story curated by UHAI-EASHRI.

View the illustrated story here.

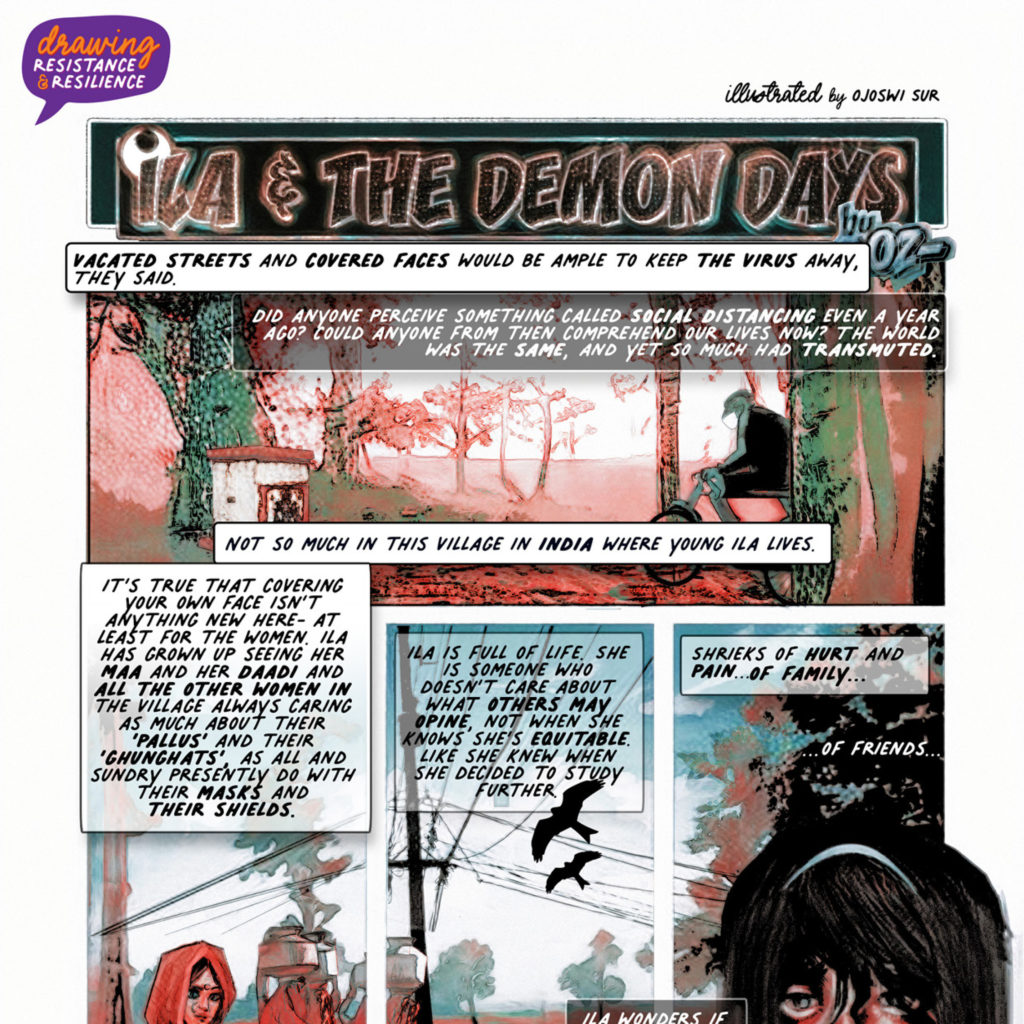

8. Ila and the demon days

There are several ways to resist – art, writing, on-ground mobilization, love, sex, friendship, theatre..

When Ila, a college student, witnessed violence in her home and neighborhood being perpetuated by men upon women and girls during the COVID-19 lockdown, she knew she could not be a bystander. Ila had been a part of the SELF academy organized by CREA where she had built her capacity to organize in the face of oppression.

‘SELF academy gave me the lens’ – Ila got together with some of her friends and approached her college to grant them an ‘essential services travel pass’ so they could conduct sensitization sessions in their communities.

The college was a station point for migrants returning home and had the authority to grant travel passes. Ila explained to them that curbing the violence is an essential need and it was impacting the physical, sexual and mental health of women and girls and the college granted them the pass. Ila used the medium of theater (she organized out street plays/ nukkad naataks with her friends over 10 days) to sensitize communities on the issue of GBV.

Theater worked as a medium to get the point across. She received messages from several women informing her that the violence at home had reduced after the men watched the street play.

Artwork by OZ.

Story curated by CREA.

View the illustrated story here.

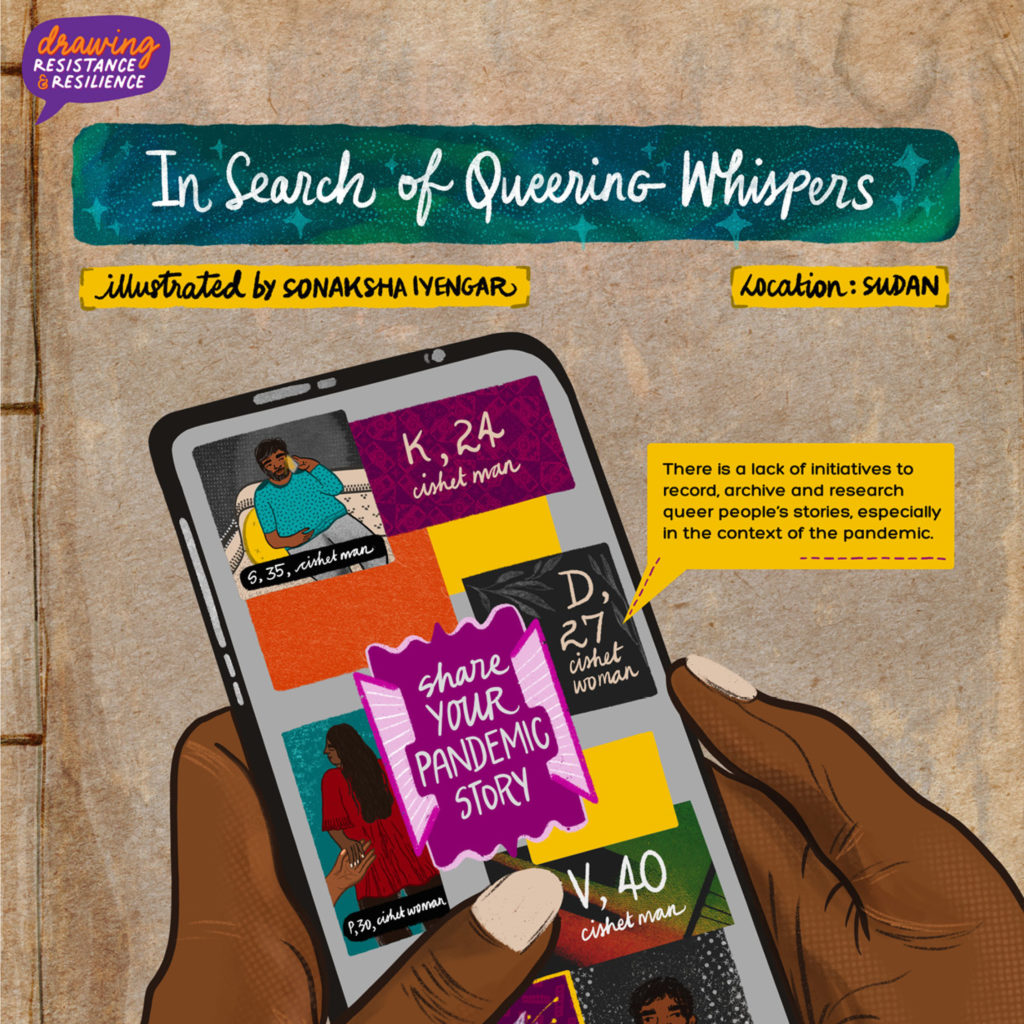

9. In search of queering whispers

Documenting cases of violence in countries that mistrust the development sector.

TW: Suicide

NGO’s have to work under intense state scrutiny in Sudan so the work of addressing gender-based violence against women and LGBTQI+ persons is hampered at the onset due to unavailability of detailed documentation on the prevalence of GBV cases. Activists and organizations covering the region rely on local networks and ‘word of mouth’ for information and our Sudanese partners reported that the situation became dire in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic as the crisis was compounded with the on-going geo-political conflict in Sudan and the MENA region.

In the words of our partners, “the number of GBV incidents against women and LGBTQI+ individuals during the lockdown are shocking, especially familial violence upon women and LGBTQI+ individuals stuck at home during the lockdown, which have sometimes resulted in the persons committing suicide”, but since there is no data to cite, it becomes difficult to call for an intervention.

Our partners have been working on developing legal and socio-political support networks using the limited means available. However, their reach has been restricted due to the lockdown and security threats. Additionally, anyone working on LGBTQI+ rights faces very serious consequences in Sudan.

The communities, however, are resilient and have been documenting and addressing GBV cases as best as they can. The need for establishing forums that can document, archive and present data to global human rights networks is highlighted.

Artwork by Sonaksha Iyengar.

Story curated by AFE.

View the illustrated story here.